Abstract:

The value of a statistical life (VSL) is the most influential single parameter used in calculating the benefits of governmental regulations. While there are some interagency differences, there is a commonality in the conceptual approach, the central role of mortality risk valuation in benefit assessment, and the general range of valuations used. Corporate risk decisions are based on a less rigorous risk analysis procedure. As typified by the General Motors ignition switch recall problems and the company’s lax corporate safety culture, there is often little systematic corporate balancing of cost and risk. This suppression of safety concerns may be attributable to the adverse experiences automobile companies had after conducting risk analyses that valued fatalities based on damages awards for wrongful death, and in response juries levied blockbuster punitive damages awards. Instead, companies should adopt the VSL in its product risk decisions. Companies should also be provided with a safe harbor reference point for responsible risk decisions. Regulatory agencies should use the VSL in setting regulatory sanctions.

...

The value of a statistical life (VSL) is the most influential economic parameter used in the evaluation of governmental regulations. The necessity for valuing mortality risks in benefit-cost analyses arises from the limitations in societal resources, coupled with substantial opportunities to promote health and safety both through private decisions and government policy. Recently, mortality risk benefits have comprised the preponderance of the benefits of all new major governmental regulations, particularly due to the efforts of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT).

The value of a statistical life (VSL) is the most influential economic parameter used in the evaluation of governmental regulations. The necessity for valuing mortality risks in benefit-cost analyses arises from the limitations in societal resources, coupled with substantial opportunities to promote health and safety both through private decisions and government policy. Recently, mortality risk benefits have comprised the preponderance of the benefits of all new major governmental regulations, particularly due to the efforts of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT).

In this article, I review the pivotal role that the VSL plays in government policies and examine how the VSL could also serve a constructive function in corporate risk decisions adopting a benefit-cost approach.

There is no conceptual barrier that limits the application of the VSL concept to valuing outcomes resulting from government policy decisions. Most of the estimates of the VSL in the economics literature are based on revealed preference studies of the risk–money trade-offs reflected in private decisions.

In lieu of revealed preference estimates, economists may attempt to create simulated market trade-offs using stated preference methods, but the focus remains on individual preferences for personal risks.

...

The meaning of the VSL can be illustrated using a simple example. Suppose that there is a 1=10,000 fatality risk to 10,000 people. Consequently, there is one expected death that will occur to this group.

Assume that each person in the group would be willing to pay $900 to eliminate the risk. Then collectively, it would be possible to raise $900 from each of the 10,000 exposed individuals to avert the random death, leading to a total amount of $9 million to avert the one expected death.

Viewed in value per unit risk terms gives a valuation: $900=(1=10,000) D $9 million. This trade-off rate per expected death serves as the VSL. For small changes in the risk level, the VSL should be the same whether people are paying for small decreases in the risk or being compensated for a small increase in the risk. This theoretical prediction is borne out in labor market data.

...

...

The dominant approach to estimating the VSL utilizes evidence on wage–risk trade-offs in the labor market. The underlying theory ... dates back to 1776 with Adam Smith’s theory of compensating differentials: Workers demand a premium for jobs that are unpleasant or pose additional risk....

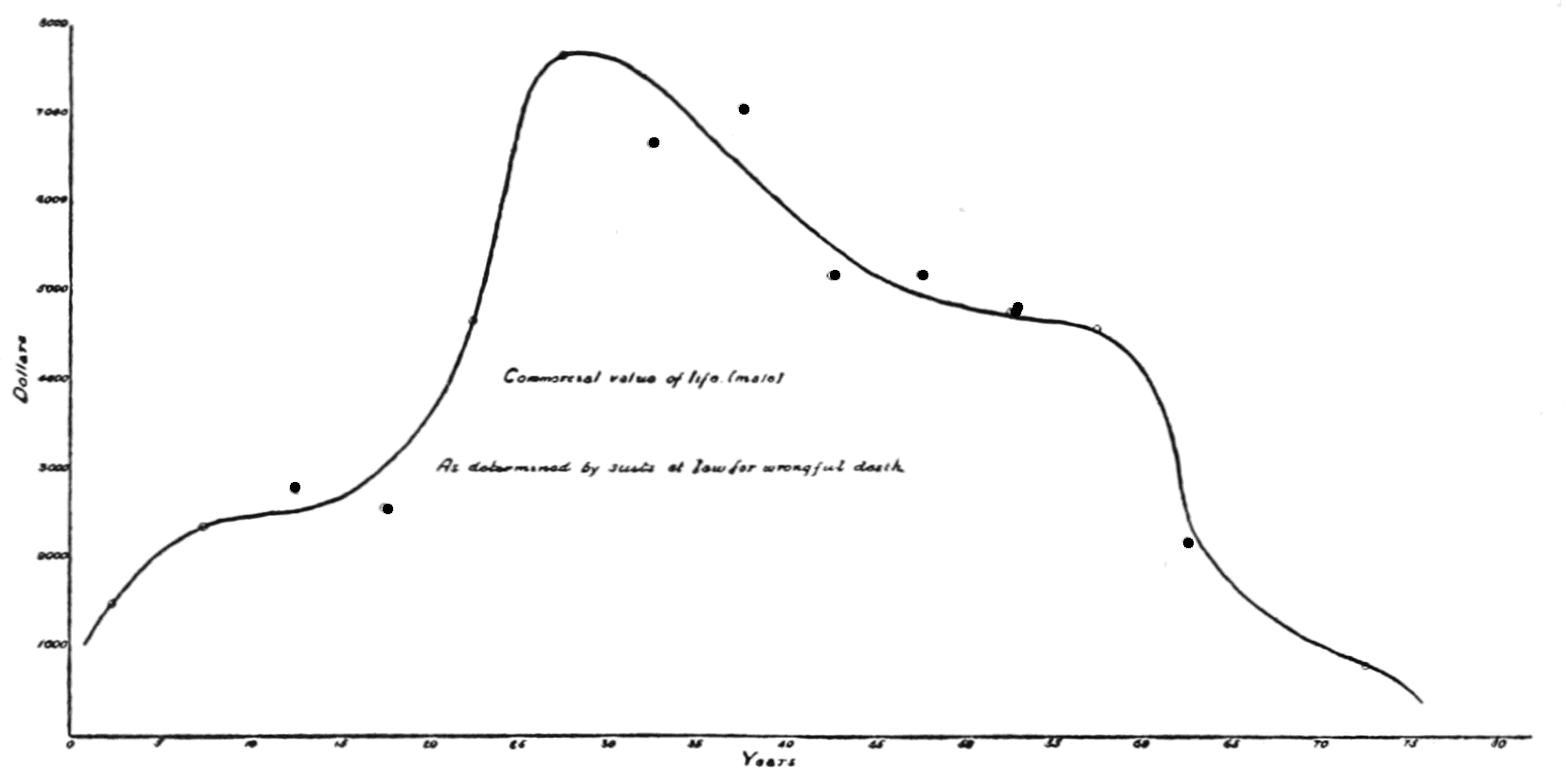

| |

| from "The Commercial Value of Human Life" By Marshall O. Leighton Popular Science Monthly; June, 1902 http://tinyurl.com/qyhc8do |

There is now a substantial economics literature that estimates the VSL from labor market decisions. Controlling for other aspects of the job, how much pay do workers get for incurring extra risk? In some instances, the risks workers face are substantial. Fictional characters such as Jack Bauer in the television antiterrorism series represent extreme examples of risk. Coal miners and deep sea fisherman are nonfictional examples of workers who incur relatively large risks. Although such dramatic risks are not the norm, few workers’ jobs are risk-free. In my early studies of VSL using data from the 1970s, the average annual worker fatality rate from job-related risks was 1=10,000. At present, the annual worker fatality risk averages about 1=25,000. The trade-offs for facing risk are sometimes explicit. For example, elephant handlers in the Philadelphia Zoo received an annual wage premium of $1,000 because elephants pose the greatest risk to zookeepers. Firefighters who battled the fires in Kuwait received $500,000 per year. More typically, workers receive a modest premium for the relatively low risks that they face on the job.... One can also estimate the cost–risk trade-off from product choices. The switch to smaller, more fuel efficient vehicles has killed thousands of motorists, but in return for these greater risks consumers have reduced their gas bills.

The average VSL based on the revealed preferences in the labor market yields a U.S. value of about $9 million. Thus, a worker facing a risk of death of 1=10,000, as in our example above, requires $900 in extra pay per year to face this risk. For the current average annual death risk of 1=25,000, the additional wage compensation is $360.... There is substantial heterogeneity in the VSL with workers in high risk jobs having a VSL far below $9 million and workers in lower risk jobs having a VSL of $20 million or more....

The average VSL based on the revealed preferences in the labor market yields a U.S. value of about $9 million. Thus, a worker facing a risk of death of 1=10,000, as in our example above, requires $900 in extra pay per year to face this risk. For the current average annual death risk of 1=25,000, the additional wage compensation is $360.... There is substantial heterogeneity in the VSL with workers in high risk jobs having a VSL far below $9 million and workers in lower risk jobs having a VSL of $20 million or more....

A principal characteristic that drives differences in estimates of VSL is the level of individual income. Safety is a normal good, and more affluent consumers place a greater value on safety. Across the U.S. working population, the estimates of the income elasticity range from 0.5 to over 1.0.... Countries with lower per capita income than the United States, such as India, have lower estimated levels of VSL.

The landmark event that led to the widespread adoption of the use of VSL by government agencies can be traced to the debate over the hazard communication regulation proposed by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in 1982. In its regulatory impact analysis, OSHA viewed the expected lives saved as being too sacred to value. Instead, OSHA calculated the “cost of death” associated with these prevented fatalities.

...

Which studies the agency relies upon in setting its VSL varies across agencies. At one extreme, the agency may rely on a single best estimate from a reliable labor market study, as in the case of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. An intermediate case is the U.S. Department of Transportation (2014), which derives its current VSL of $9.2 million relying on an average of the estimates from labor market studies using the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) data, which is the current gold standard in occupational fatality data.

The EPA has a long history of interest in VSL issues governed primarily by a series of meta-analyses,

which comprise primarily the revealed preference estimates but also may include stated preference estimates.

The EPA has a long history of interest in VSL issues governed primarily by a series of meta-analyses,

which comprise primarily the revealed preference estimates but also may include stated preference estimates.

...

Much of the focus of the recent economics literature has been on estimates of the heterogeneity of VSL with different personal characteristics, such as age. Efforts to incorporate this heterogeneity in policy evaluations have not been successful. The EPA performed a sensitivity analysis of its Clear Skies initiative using an age-adjusted VSL that reduced the VSL for fatalities to those over age 65 by 37% using results from stated preference research in the United Kingdom. The public outcry over the use of a “senior discount” led to the abandonment of this exploratory effort.

...

...

I believe the current economic approach strikes a reasonable middle ground between infinity and lifetime earnings, with current VSL estimates based on consumer preferences being in the vicinity of $9 million.

Much of the focus of the recent economics literature has been on

estimates of the heterogeneity of VSL with different personal

characteristics, such as age. Efforts to incorporate this heterogeneity

in policy evaluations have not been successful. The EPA performed a

sensitivity analysis of its Clear Skies initiative using an age-adjusted

VSL that reduced the VSL for fatalities to those over age 65 by 37%

using results from stated preference research in the United Kingdom. The

public outcry over the use of a “senior discount” led to the

abandonment of this exploratory effort

GM CEO Mary Barra ... indicated that GM had done a recall assessment for which they assumed the cost was about $100 million back in 2007. She did not indicate the estimate of any adverse effects that would have been prevented. Suppose that for purposes of illustration we use the 124 fatality estimate that GM now attributes to the defective switch, and set aside the nonfatal injuries and property damage for purposes of this calculation. What would the estimated benefits have been? If you take the current VSL estimate used by DOT of a $9.2 million VSL and multiply it by 124 deaths, the estimated benefits equal $1.141 billion. Alternatively, if you take my meta-analysis VSL number with Joseph Aldy of $7 million (year 2000 dollars), which understates the inflation-corrected VSL level at the time of the recall decision, then the mortality risk benefit of doing the recall is $868 million. In each case, the mortality risk reduction benefit exceeds the $100 million cost estimate, so it easily passes the benefit-cost test.... On benefit-cost grounds wholly apart from their legal obligations, GM should have done the recall. What is particularly striking is that GM did not do any such analysis. While there apparently was at least an attempt to develop a rough estimate of the cost of a recall, there is no evidence that any employees sought to assess the safety benefits of a recall.

...

...

A prominent starting point for considering the potentially costly ramifications of risk analysis is the tort liability case involving the Ford Pinto, Grimshaw v. Ford Motor Co. This entry level vehicle had a shortcoming in that if you are driving a Ford Pinto and somebody hits your car from the rear, there is a good chance the car will have a fire, leading to potential burn injuries and possibly death. Ford was aware of the fire-related risk from the gas tank placement and had done a benefit-cost analysis of the desirability of moving the gas tank so that there would not be a fire upon rear impact. The Ford analysis used $200,000, the average court award for wrongful death cases at that time, as the benefit value for preventing each expected death. The Ford analysis concluded that the cost of $137.5 million exceeded the benefits, so the company did not move the gas tank.... The jury not only found Ford liable for the death, but also levied a $125 million punitive damages award to punish Ford for its behavior.... Chrysler undertook similar risk assessments and in one case, Jimenez v. Chrysler Corp., was hit with a $250 million punitive damages award.... General Motors engineer, Edward Ivey, applied his engineering training to undertake a benefit-cost analysis of moving the fuel tank. Similar to the Ford analysis approach, he did a benefit-cost analysis using $200,000 per fatality based on the wrongful death awards and concluded the costs exceeded the benefits. As a result, the company did not alter the placement of the tank. In the post-trial discussions, the jurors indicated that because GM officials had done the analysis, the company knew there was a risk. That they knew of the risk was the constant refrain among the jurors who were interviewed. The jury awarded $101 million in punitive damages

...

Policy reform also includes a meaningful role for the VSL in terms of the regulatory sanctions. National Highway Transit Safety Administration (NHTSA) penalties are currently capped at $7,000 per violation, with a limit of $35 million total penalties for a related series of violations. These are trivial amounts. The appropriate deterrence value for known risks is the VSL. So at $9.2 million a life and 124 people killed, the amount of money you would need to generate the appropriate incentives is $1.141 billion. Rather than using $7,000 per violation, NHTSA should use the VSL to set the penalty level in the case of fatalities, boosting the scale of penalties by three orders of magnitude. Changing the penalty structure in this way would require a change in the agency’s legislation.

...

...

Policy reform also includes a meaningful role for the VSL in terms of the regulatory sanctions. National Highway Transit Safety Administration (NHTSA) penalties are currently capped at $7,000 per violation, with a limit of $35 million total penalties for a related series of violations. These are trivial amounts. The appropriate deterrence value for known risks is the VSL. So at $9.2 million a life and 124 people killed, the amount of money you would need to generate the appropriate incentives is $1.141 billion. Rather than using $7,000 per violation, NHTSA should use the VSL to set the penalty level in the case of fatalities, boosting the scale of penalties by three orders of magnitude. Changing the penalty structure in this way would require a change in the agency’s legislation.

...

Much of the controversy over the past three decades with respect to the use of the VSL to value mortality benefits has stemmed from a misunderstanding of what the economic value of mortality benefits actually is. When I first generated VSL estimates in the 1970s, there were critics at each end of the valuation spectrum. On the one hand, people would argue that the VSL number should be infinite so that the government should place an infinite value on risks to lives. At the other

extreme, some people argue that the multimillion dollar numbers are way too high because they exceed the present value of lost earnings. Following this logic, how could lives be worth more than what people earned? I believe the current economic approach strikes a reasonable middle ground between infinity and lifetime earnings, with current VSL estimates based on consumer preferences being in the vicinity of $9 million.

extreme, some people argue that the multimillion dollar numbers are way too high because they exceed the present value of lost earnings. Following this logic, how could lives be worth more than what people earned? I believe the current economic approach strikes a reasonable middle ground between infinity and lifetime earnings, with current VSL estimates based on consumer preferences being in the vicinity of $9 million.

A recurring lesson for public and private decisions is that monetizing benefits makes them matter. So if we start leaving these numbers out of the analysis because lives are too sacred to value, we will be back in the pre-VSL era and lives will be less highly valued than they are now. The use of VSL in benefit-cost practices is well established for government agencies. The remaining challenge is to promote the use of benefit-cost analysis in corporate risk management decisions.

...

by W. Kip Viscusi; University Distinguished Professor of Law,

Economics, and Management, Vanderbilt University, 131 21st Avenue South,

Nashville, TN 37203, USA, Phone: +1 615 343 7715, Fax: +1 615 322 5953,

e-mail: kip.viscusi@vanderbilt.edu.

Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis of the Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis via Cambridge University Press http://journals.cambridge.org

Volume 6, Issue 02; Summer, 2015; pages 227-246; Published online: 19 August 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/bca.2015.40

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/bca.2015.40

This article is based on the author’s presidential address at the Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis conference, March 19, 2015. Glenn Blomquist and Bill Hoyt provided valuable suggestions.

No comments:

Post a Comment